She is called a “rebel nun.” She is called too unconventional and uncompromising, and even a radical, by “traditionalists.” It is true. She is a radical, a rebel, and unconventional—but in exactly the same way that Jesus is also these things. She was absolutely uncompromising with injustice and hypocrisy. She was radical in that she fully believed in following Christ’s radical commandment to love all people. She said that at the Last Judgment, she would not be asked how many prostrations she had made, but whether she had fed the hungry, clothed the naked, and visited the sick and prisoners in jail. She believed so totally in the sacrificial power of love, that she willingly walked the path to Golgotha with Christ for many years prior to her freely accepting the cross of martyrdom in the Nazi Ravensbrück concentration camp on Western Good Friday and the eve of Easter. She was in one of the last groups to be gassed and burned to ashes just before the allied forces liberated the camp. Not long after that, World War II ended: the Nazis were defeated and their savage, brutal, dehumanizing and hideous systematic extermination of Jews — and Christians, such as Mother Maria, who dared to help them — ended. It is believed that she willingly joined that last group to be exterminated in order to give strength and comfort to the despairing, and perhaps to take the place of another. This is not surprising, because she had been giving her life for others for years, in order to help the poor, the sick, the suffering, the destitute, the despairing. Ever since her youth, she had been a pioneering and passionate idealist, and felt ready to give her life in the name of justice and to help the poor and down-trodden; she had premonitions since her youth that her life would end on a martyr’s cross of fire.

Some accuse her of being a “bad” nun, because she didn’t strictly adhere to the external forms of conventional monasticism. On the contrary, she exemplifies what monastics and all Christians are commanded to strive for: she had totally died to herself, and lived for God alone, serving others in need with unconditional love and compassion. She had emptied herself of self, just as Christ emptied Himself by incarnating as a human being. She totally gave of herself to the world, offering her heart filled with God’s love to all those in need, just as Christ gave of Himself on the cross out of love, and gives of Himself to us in the Eucharist. She had completely died to herself and to the world, so that Christ could live in her, and through her, to give Himself to the world. She put into daily practice the words of St. John the Forerunner and Baptist: “I must decrease and He must increase.” She didn’t live in a monastery, but lived in the world, in order to more fully minister to suffering people: the world was her monastery, as her bishop, Metropolitan Yevlogii, stated. For this reason she is an exceptional model for us who also live in the world, and strive not to be of the world—a daily struggle for those who are totally committed to following Christ.

What was Mother Maria life’s journey that led her to martyrdom? Elizabeth (Liza) Pilenko was born in December 1891 into a Russian aristocratic family that owned land and vineyards in the city of Anapa, by the Black Sea in southern Russia. She was an idealistic, devout, talented, precocious and impetuous youth. During her teens, her idealism and desire to help the Russian people led her to be temporarily involved with social revolutionaries. Liza was a pioneer even from her youth. She was a talented poet, writer, artist, intellectual—an educated and creative thinker, when this was rare for women. During her precocious early and mid-teens, her friends were the pre-Revolutionary leaders of the St. Petersburg intelligentsia — poets and writers. She attended the University and was the first woman to ever complete studies at the St. Petersburg Theological Seminary. But she married impetuously, idealistically thinking that she could save the young man from despair and alcoholism. The bad marriage quickly ended; a daughter, Gaiana, was born. Late World War I saw her back home in Anapa, running the family’s estate, vineyards and wine-making business. Just as the Revolution reached the South, she became the mayor of her city of Anapa — unheard of for a woman. Liza handled this task with great skill and wisdom, and it seems that she drew upon this experience in her later work in Paris. Of course, the Revolution changed everything in her life, as it did for all Russians. She experienced a great deal of suffering, first at the hands of revolutionaries in Russia, then, just barely escaping from Russia in 1921 with her daughter and her mother, Sophia, she lived a terrible life as a refugee in Istanbul, Greece and Serbia. She married Daniel Skobstov, whom she had met in Anapa before their escape, and two more children were born: Yuri, who was to die in 1944 in a Nazi concentration camp, and Anastasia (Nastia). In 1923 the family eventually reached Paris, which became a major center for many Russians who fled the Communist Revolution. In the 1920’s and 30’s the poverty, illness and despair of émigré life was almost overwhelming.

In 1926 Liza’s youngest child, Nastia, died of meningitis, with Liza by her side. This was a major turning point in Liza’s spiritual life. The reality of Christ’s love filled Liza’s heart, and she committed her life to serving Christ by serving the needy and destitute. She started working with the Russian Student Christian Movement that provided educational, spiritual and material aid to thousands of destitute Russian refugee émigrés in France. She became friends with the leaders of the Russian Orthodox community in Paris, including theologians Fr. Sergei Bulgakov, Prof. George Fedotov, Prof. Nikolai Berdiaev, Fr. Lev Gillet, and Metropolitan (Bishop) Yevlogii, the head of the Russian Church in Western Europe. She traveled around France, supposedly to give Russian Student Christian Movement lectures, but usually ended up doing pastoral, diaconal work— listening to and counseling despairing people.

She meditated and prayed about how she could better serve God’s neediest people. Should she become a nun? She spoke with the greatly admired Metropolitan Yevlogii, who supported and encouraged her call to the monastic path. Having already separated from Daniel Skobstov in 1927, a divorce was granted. In 1932 Liza was tonsured a nun by her bishop and given the monastic name of Maria. She immediately established a “hostel” for the homeless and destitute at Villa de Saxe in Paris. She quickly outgrew this house, and two years later she moved to 77 Rue de Lourmel, which remained the center of her work until she was arrested by the Nazis in 1943. It was here that hundreds of people were fed at a “canteen” every day, and where homeless and crushed and wounded souls could find shelter. She enlisted volunteers to help her raise funds, to gather and prepare food every day, and to shelter those who needed her help. She converted a stable into a chapel. “Orthodox Action,” the Orthodox successor to the Russian Student Christian Movement, had its home here at Lourmel, and on Sunday afternoons, some of the most noted clergy, theologians and intellectuals of Paris would gather for lectures and discussions. Mother Maria was right at home in the midst of them. She continued her trips to other parts of France, to minister to destitute and despairing Russian émigrés, wherever she could find them, especially helping those with tuberculosis and those in mental hospitals. In 1936 Mother Maria experienced yet more personal sorrow and suffering: her older daughter, 21-year old Gaiana, who had chosen to return to her Russian homeland the previous year, died in Moscow of typhus. Now, as throughout her life, Mother Maria expressed her deepest thoughts, pain and struggles in her poetry. Being a gifted writer of both poetry and prose, she wrote many articles for newspapers and journals that brought public awareness to the desperate needs of Russian refugees in France, resulting in some necessary political changes, and attracting donations to help those in need from benefactors in France and other countries, especially Britain and the USA.

In 1939 Metropolitan Yevlogii assigned a young married priest, Fr. Dimitri Klepinin, as the pastor of the Lourmel church, and he became Mother Maria’s close ally and co-martyr in the Nazi camps in 1944. In 1941 Hitler invaded and occupied France. Jews and Russians were required to be registered. By 1942 things got much worse, and the open attacks, arrests and deportations of Jews began. Mother Maria’s diaconal-pastoral ministry at Rue de Lourmel intensified with the rise of Nazi power. Fearlessly risking their lives everyday, Mother Maria, Fr. Dimitri, her son Yuri, and other members of Orthodox Action, did everything possible to help save Jews, working closely with the underground French Resistance against the Nazi satanic power. Mother Maria believed that monastic life was meaningless if it were not an incarnation of love for God and one’s neighbor. Therefore they provided forged baptismal certificates for Jews in order to smuggle them out of Nazi-occupied France, sheltered Jews at Rue de Lourmel, and transported Jews to safe places of refuge. They saw the image of Christ in every needy person, and firmly believed that Jesus would have done the same as they were doing. Finally the inevitable happened: in early 1943 Mother Maria, her 21-year-old son Yuri Skobstov, and Fr. Dimitri Klepinin were arrested and imprisoned by the Nazis. Yuri and Fr. Dimitri both died of disease within 4 weeks of their transfer to a concentration camp. But 53-year-old Mother Maria, being accustomed to many years of ascetic deprivation, actually managed to survive for two years. During this time she willingly accepted her situation and never complained. She gave freely of herself, offering spiritual and emotional support and strength to many others in the camp. The Nazis did everything possible to dehumanize the prisoners and turn them into beasts. But thanks to Mother Maria, many preserved their souls intact as they went to the gas chambers. On March 31st, 1945, the world lost a truly great soul when the Nazis gassed her and burned her body in their ovens. After the war many survivors testified to Mother Maria’s heroic, martyric and self-sacrificing example in the camps. May we also be inspired by her example, and joyfully accept Christ’s radical challenge of living a life of self-emptying love of neighbor, bearing our crosses, and living in the world, but not being of the world.

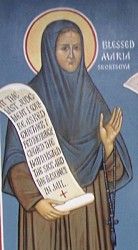

Postscript: Fr. Sergei Hackel—priest, professor and author, creator of the journal Sobornost, who emigrated with his mother to England in 1940 at the age of eight to escape the Nazis—worked for over forty years to have Mother Maria Skobstova of Paris universally glorified/canonized as a saint. In 1965 he published his first edition of the life of Mother Maria, and in 1982 published his second edition, entitled Pearl of Great Price. His efforts finally bore fruit, and in May 2004, he participated in her formal glorification (and that of her son, Yuri Skobstov, and her priest, Fr. Dimitri Klepinin), held at the Cathedral in Paris. He wore vestments that Mother Maria herself had embroidered. He reposed nine months later, on 9 February 2005, at the age of 73. March 31, 2005, approximately one year after her canonization/ glorification, marked the fortieth anniversary of the martyrdom of Mother Maria. Her icon shown here (above) was written/painted by Archpriest Fr. Theodore Jurewicz at St. Innocent Church, Redford, Michigan, in October 2004.

By: Sister Ioanna, St. Innocent Monastic Community, Redford, Michigan